- Home

- Christopher Wilson

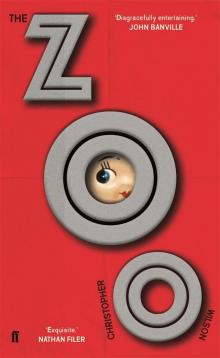

The Zoo Page 4

The Zoo Read online

Page 4

His tone is gruff. He barks strict instructions, concerning his comforts. He is brisk, needy and ungrateful. You can tell he’s used to getting his own way and having folk bend to his will. He seems to think I’m here just to do his bidding and benefit him.

He has me plump his pillows and lay the blanket over his legs. He has me fetch his pipe and a box of cigarettes from the desk. He wants water pouring into one glass, and vodka decanted into another.

He insists to know if the seals are unbroken on the bottles. Is the cellophane wrapping intact on the packet of cigarettes?

He wants me to taste from the glass before he will drink. He wants me to lay out the pieces on the draughts board. He selects the white piece for himself.

‘I suppose everyone tells you,’ I say, ‘that you look in some ways like Comrade Iron-Man …’

‘There is a facial resemblance.’ He smiles a quick, tight smile, then promptly stifles it, so the impression of friendliness is just a brief visitor, and slides right off the far side of his face.

‘Yes. But many differences too …’ I say.

‘Differences?’ He frowns. ‘What differences are those?’

‘Don’t take offence,’ I say, ‘but Comrade Iron-Man is a big man. A handsome man. He is a tall, straight-backed man. He is younger. His hair is dark, not silver. His skin is smooth and flat. But you are an old man. You are short. You have scabs on your cheeks …’

‘Are you some expert on Comrade Iron-Man? Do you know more about him than me?’

‘Not an expert, exactly,’ I say, ‘but I notice things. I have seen the photos, the posters, the newsreels. And I hear people talk about him.’

‘And what do they say?’

‘No one has a bad word,’ I say. ‘Not in public. Some people seem to love him. And the rest are scared of being shot, or sent to the camps. Everyone’s too terrified to talk. It’s suicide to tell the truth.’

The Sick-Man does not welcome these comments. He does something twitchy with his nostrils. He raises his brows, narrows his eyes and regards me steadily, getting to make me feel small, trying to make me blink first.

He says that I misunderstand. Comrade Iron-Man is an idea, not a man. An inspiration. Not a simple, single person. He is a beacon to the people. He is a political necessity. He can be all possible things – younger or older, taller or shorter. He can be kind or stern. Harsh or forgiving. Old and wise or younger and vigorous. It depends on the circumstances and political needs of the time.

He says Comrade Iron-Man is a complexity that cannot be bound by biology or convention, or caged by a single body.

‘Yes, they say it can’t be easy for Comrade Iron-Man,’ I agree. ‘Everyone is scared of him. People are afraid to tell him the truth. And he is only human, after all. He gets used to getting his own way. And it is not his fault if people do such bad things in his name. They say there have been times in history when it’s been safe to speak. But now is not one of them …’

‘People who say such things are loose-tongued fools with a death-wish,’ says the Sick-Man. ‘And you are a certifiable idiot.’

‘Yes, sir, and no, sir,’ I explain. ‘It’s true I’ve a damaged mind. It’s a medical condition. But it doesn’t make me a fool.’

I tell him about my accident and how it touches upon my mind. I lean forward so he can see, through my Pioneers’ crew-cut, to the long ridge of scar on my cranium, and I show him my twisted arm.

‘That’s nothing … Look here …’ He rolls up the sleeve of his night-shirt to show his bent left arm. ‘As a child, I was hit by a horse-drawn carriage.’

‘Yes,’ I say, ‘the same. The same. I was hit by a horse-drawn milk cart, then by an electrical tram.’

Clearly, we have much in common, the Sick-Man and I.

‘Were you ever struck by lightning, like me? On Sparrow Hills? What is your favourite colour?’ I ask. ‘Do you have a lucky number? And what is your football team? Do you have a favourite rodent?’

He just grunts. If he has any strong preferences in these regards, he isn’t telling.

‘Why are you sad?’ I ask.

‘Me? I’m not sad.’ He sounds gruff. He frowns as if taken aback. He wipes the glistening corner of a moist eye. ‘Not me.’

‘There’s sadness,’ I say, ‘here in this room. ‘Thick. All around.’

‘There is?’ He looks over his shoulder, as if concerned.

‘Thick, smoky, choking sadness. It clogs your breath. It makes me cough. And I feel there must have been many deaths around you …’

This is my intuition. You see, sometimes I know things about people, without knowing how I know them.

‘It’s true,’ he concedes. ‘Many are gone … passed on before me … Comrades, family, friends …’

He stares me full in the face.

‘You are an odd child,’ he says, softening. ‘You have a strange face … A kind look …’

Then, I feel it happening again.

Out of the blue, as if a switch has been flicked, he starts, like all the others, telling me things – personal, secret, unnecessary things – things I’d rather not hear.

As usual, it starts badly. And then gets worse.

He sounds in a very dark, thoughtful mood.

‘They say I killed Comrade Lenin,’ he begins.

‘They do?’ I’m over twelve years old, but I’d never heard that one before.

‘They said I poisoned him when I gave him his injections.’

‘Oh?’

‘For syphilis. Because he opposed my election as General Secretary.’

‘Yes?’

‘To get him out of the way. To give him a massive stroke. But I never did.’

‘Good,’ I say. ‘Good.’

‘And they say I killed my wife …’

‘Yes?’ I ask. ‘They do?’

‘But I did not kill my wife.’

‘No?’ I say. ‘That’s good.’

‘I did not shoot her.’

‘No?’

‘She shot herself.’

‘Why so?’ I ask. After all, when people take the trouble to tell you these unnecessary, personal things, they expect you to cobble a concern.

‘Just to spite me.’ He shakes his head at the meanness of wives.

‘Oh,’ I nod. As if it all makes sense to me.

‘My son, Arkady, tried to shoot himself too.’

‘That’s a shame,’ I say.

‘But he missed. More than once. Just grazing his temple.’

‘Good,’ I say, but it turns out this is a very poor, ill-considered answer.

‘Good?’ he sneers. He imitates me with a high-pitched tone. ‘Good? How is it good? To miss shooting yourself? Twice? With a pistol? From a distance of five centimetres?’

‘I don’t know,’ I have to admit. Put like that, it does seem aimless or insincere.

‘My life has been blighted by selfish relatives. They think they can get my attention, just by shooting themselves.’

‘They do?’

‘They try to kill themselves just to spite me. And succeed when I’d rather they fail. And fail when I’d prefer they succeed.’

‘I’m sorry …’ I console.

‘And I’ve been utterly shamed by useless sons …’

‘Useless?’

‘Arkady gets captured by the Germans. They offer to swap him for one of their generals we’ve caught. Of course, I say “No”.’

‘Why?’

‘Why would I make such a swap? Giving something of value for something worthless? A great warrior for some useless relative, with only sentimental value?’

‘Oh.’

‘Then my other son, Viktor, does something beyond stupidity. He loses something important that isn’t his to lose.’

‘Important?’

‘The National Ice-hockey Team.’

‘Loses them?’

‘He orders their plane to fly off in a snowstorm. Of course, it crashes on take-off. Everyone’s killed �

��’

‘That’s a shame,’ I say.

‘He never tells me. He thinks to hide it from me. He just picks another team to play in their place.’

‘Oh.’

‘Viktor,’ I tell him, ‘you are beyond hopeless. You are worse than useless. I give you one last warning. And never, ever, lose the National Team again … They are the world champions. It is the sport of the Motherland. Ice-hockey players like those don’t grow on bushes.’

‘Did he change his ways?’

‘Yes. He’s transformed himself into a hopeless drunk.’

‘Do you have any daughters?’

‘I have a daughter,’ he concedes, ‘called Nadezhda. She is sweet-natured, useless and soft in the head. She is a horizontalist. She spreads her legs for conmen and Zionists. She wants the world to lie on her belly. She wants to have babies by the enemies of the State.’

‘Yes?’

Sometimes, in the face of a long disclosure, it is enough just to say ‘Oh’, ‘Yes?’, ‘No?’, ‘Really?’, or ‘Is that so?’, or ‘You don’t say.’

‘Why am I telling you all this?’ he demands, as if I’m to blame for his ugly, needless confessions.

‘I have this effect.’ I confess it. ‘People tell me things … even though I never ask them … and don’t want to hear. Aunt Natascha says I could be an interrogator for State Security. If they only cared for the truth …’

The Sick-Man reaches out, plucks three Herzegovina Flor cigarettes from the pack and rips them open, scrunches them in his palm, discarding the paper and cardboard tube, tamping the tobacco into the bowl of his pipe. Then he lights up.

I sense he resents me now, for loosening his secrets, and touching upon his pain.

‘Idiot boy,’ he mutters, under his breath.

‘Me, sir?’

‘You are a simpleton. You are very stupid. They must call you mean names at school …’ the Sick-Man says. ‘Like Moron, Idiotnik, Arse-wipe and Cretin?’

‘Yes,’ I admit it, ‘they mostly call me Retard, Snot-Face and Yuri-Shat-His-Pants. But when I first join Boris Tiverzin tells the rest of the class that I’m a biology experiment, made of bits of dead animal from my father’s zoo, all sewed together, then brought to life by a lightning bolt … But, actually, this isn’t even half-way true …’

I explain how it is to the Sick-Man.

Because I was run over by a milk truck, and then by a tram, and as a toddler I once climbed through the bars into a cage to play with the Siberian tigers, and scratch their bellies, and ride on their backs, but never got hurt, and fell off a roof, but into a passing trailer loaded with straw and elephant dung, which broke my fall, and then got struck by lightning on Sparrow Hills, which made my hair stand up on end for months, Papa used to call me his Koschei, The Deathless, after the character in the fairy stories who could never be killed because he kept his soul apart from his body, inside a needle, in an egg, in a duck, which is inside a hare, which is inside a crystal chest, which is buried beneath an oak, on a deserted island, in the middle of the ocean.

And it always made me feel protected, so that although I got damaged I was always guarded and in some ways special.

The Sick-Man nods. He understands.

‘Once, long ago, they used to call me Scab-Face,’ he says. ‘But they do not call me that any more. They used to laugh at me. But they don’t laugh at me now …’

‘I suppose not,’ I agree.

‘Enough futile recollections.’ He taps the draughts board with the tip of his pipe. ‘Now, we shall play Shaski.’

Soon we are sunk in our game, wrapped in a cloud of tarry grey tobacco smog.

‘You shouldn’t smoke,’ I warn him. ‘Not when you’re half-dead already.’

‘No?’

‘Papa says it gives you smoky lungs … excites the blood and alarms your heart. Plus you should keep your draughts on the back row as long as you can.’

He just grunts.

‘Are you good at this game?’ I ask. ‘Do you have any strategy? Do you think many moves ahead?’

‘Shhh,’ he growls. He holds a finger to his lips, like Papa.

‘I am a good player, myself,’ I explain. ‘I have vision. I have tactics. So, you mustn’t mind losing to me, even though I’m a child with a damaged mind.’

He grunts. He mutters. If I beat him he will eat his feet. Both feet, he says. With horseradish dumplings. To me, this sounds a rash offer. We both look to his naked feet, laid up on the sofa. They are white, moist and pudgy, like newly made pastry. Some of his toes are joined, webbed like a duck’s foot.

Even now, after only five moves each, I can see he is approaching zugzwang. So he can only move to his own disadvantage. He must advance. But he can only move in front of my piece. Then, because of his careless spacing, I can promptly jump four pieces of his.

He reaches out to move his piece. Then he hesitates. Then he frowns. Then a sly smile forms on his face.

‘Now, I will invoke the Counter-Reactionary Defence,’ he says, banging the tabletop with his closed fist. Clearly, he thinks he has me beaten.

‘The what?’ I say.

‘The Counter-Reactionary Defence allows me to defend myself against liberal parasites and reactionary back-sliders. I can advance, and then capture, your leading, right-wing piece, if no effort has been made to correct its backward-looking tendencies, by moving it leftwards, in your past three moves.’

‘I never knew,’ I confess. I never saw it coming. In fact, I never knew this rule existed.

‘Did you think you could loiter on the right with impunity? Now …’ He pounces. ‘I can take two of yours.’

He jumps my piece. Then he jumps another piece. But I swear they were not at hazard before the Counter-Reactionary Defence came into force.

This way, he gets to the end of the board and wins a kingpiece. So, now he can zigzag back and forth, picking off my men, one by one, or two by two.

‘Your position is hopeless,’ he says. ‘You were careless. You left your flank exposed, defended only by feeble, reactionary forces. But don’t be disheartened … I am a strong player. I see new possibilities that others only guess at.’

We play some more. I am two men ahead in the second game, but he suddenly turns things round for himself, with the help of the Usual-Suspects Gambit, which is another new rule I know nothing about.

‘It allows me to imprison all your men that have formed together in the manner of a demonstration or illegal gathering,’ he explains. ‘It is standard police practice. It is social hygiene, for the good of us all.’

And then he wins the third game with the Common-Good Principle, which enables him to exile, Far North of the board, any of my pieces that threaten the well-being of the majority, by being enemies of the people.

I am dismayed. I’ve always thought of draughts as a simple game of few rules. It is daunting to keep meeting these new political regulations I’ve never dreamed of.

‘Don’t be disappointed,’ he says. ‘Shaski is practical politics. Nobody has beaten me at this game for a long, long time.’

‘How long?’

He frowns to consider. ‘Twenty-seven years, I believe.’

‘I’m not surprised,’ I say. ‘If you make up the rules as you go along …’

We sit in silence for a while.

When at last he speaks, it is to ask me if I like moving-pictures.

‘Oh, yes,’ I say, ‘I love the movies.’

He tells me this is a good, correct, Socialist answer. Movies are the most progressive forms of art. Books are liberal. Novels waste time, loitering inside the head of small, petit-bourgeois characters. They examine the trivial thoughts and inconsequential feelings of unnecessary people.

‘This boy has a sore conscience, this girl wants to visit The Kapital and marry a count. That man wants to scratch his itch …’ he says. ‘But, we do not care about a man with an itch. We do not give a shit if he scratches … Stavrogin can go hang himself. Oblomov can stay

in bed, for all I care. Pechorin can eat his horse. Anna Karenina can take in washing.’

‘Yes?’

‘We want what matters. We want to see the true events of history. The battle between the classes. The conflict of Labour and Kapital. Thesis, antithesis, synthesis … Maybe we are interested in the individual if he is a type, a man of his time, or a man in the eye of the conflict, or he is a great man who leads his people. And all this we can see in film. The action, the conflict, the groups, the peoples, as if we are watching history …’

He goes on about the foreign films that were captured during the war. Many German. Many Amerikan. Many from the film library of Joseph Goebbels himself, fellow film-lover and cohort of Hitler.

He asks me if I have watched the films of the great Communistic actor Charles Chaplin who represents the genius of the common person, playing him as a tramp, a worker, a poet and a dreamer. And who shows the cruelty of Kapitalism, and the posturing of dictators, and that life is a tragedy in closeup, but a komedy in long-shot. And that life is ruthless. So, to cope with it, you must be ruthless yourself …

I say I have not seen the films of Comrade Chaplin. Because we only see Homeland films in our Picture House. But I have been fortunate enough to have watched The Humpbacked Horse, The Fall of Berlin, The Symphony of Life and How the Heroic Workers of Novomoskovsk Achieve Their Five Year Collective Construction Targets Two Years Ahead of Plan.

‘You’ve never watched Amerikan Western movies?’ he asks.

‘What?’

‘Cowboy films. With Indians, bows and arrows, spitting, scalping, horses and shooting.’

I shrug. These things are not within my experience.

‘You should. These are an education. The Amerikan Western shows the moral emptiness, the lawlessness of Kapitalist Culture … Amerika is a wasteland, a tundra or desert. Every man carries a gun. Often there is only a single, powerful man to bring order from the chaos, or to protect the working people.

‘There are Tsars ruling Business. Kulaks controlling the land. The Cossacks are their henchmen.

‘The good characters wear light-coloured clothes, the bad characters wear dark. There is no art, no culture. So they just drink whisky, play poker and visit prostitutes. All the time they fight each other, because there is no Socialist-Solidarity or Class-Unity.

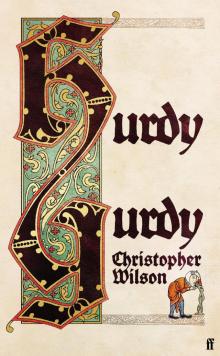

Hurdy Gurdy

Hurdy Gurdy The Zoo

The Zoo