- Home

- Christopher Wilson

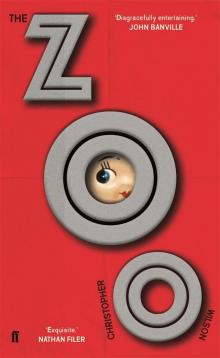

The Zoo Page 5

The Zoo Read online

Page 5

‘You know there will be a fight when the camera moves from one face to another and back again. When the camera freezes on the face, they are preparing to shoot.’

‘Yes?’

‘The greatest Western film is Stagecoach. It is directed by the great John Ford. And the greatest cowboy actors are Spencer Tracy and Clark Gable.

‘But there is an odious cowboy actor called John Wayne who has appointed himself as an enemy of the proletariat, always mocking Socialism and decrying the achievements of the Socialist Union. So, we will not be surprised if some patriotic soldier of the Union of Socialist Republics will go someday soon to Amerika and knock on the door of his home – at 4750 Louise Avenue, Beverly Hills – to silence him, once and for all, with a knife through his heart, ice-axe through the temple, or stiletto into his spine …’

*

I look around the room. I wander to the easel bearing the large map of our great and wide, beloved Homeland.

There are maybe twenty pins with titchy, triangular flags attached – red, white and blue – spreading South and East of The Kapital, and also up into The Cold Lands.

The Sick-Man follows my gaze. ‘We must find a new place for the Rootless, Zionist Cosmopolitans,’ he explains.

‘New towns?’

‘Camps.’

‘Holiday camps?’ I ask. ‘For recreation? With swimming pools, football pitches and running tracks. Like those for Junior Pioneers?’

‘Work camps,’ he says. ‘For hard work. And harder work.’

‘Rootless Cosmopolitans?’ I ask. ‘Are they the Gypsies and tramps and refugees?’

I guess he is planning new houses and new jobs for the homeless.

‘The Jews,’ he says. ‘They want to leave their Motherland. They want a home in Palestine. They always look to the Amerikans as their friends.’

‘Papa’s friend Pyotor Kolganov teaches me the piano. He’s Jewish. But he’s not rootless. He likes living in The Kapital. He’s on the third floor of his building. He said he could never move. It would be too difficult to shift the grand piano down the stairwell …’

‘There are Jews and Jews …’ the Sick-Man says. He taps his nose. ‘There are many Jewish killers in white coats, under the mask of Professor-Doctors, who plot to murder our leadership. And there are many Jewish Nationalists who are spies, agents of Amerikan Intelligence.’

‘Aunt Natascha’s friend Vasili is Jewish too. But he’s not a Spy or Killer-Doctor. He’s an attendant in a lunatic asylum.’

The Sick-Man looks away, adrift in his thoughts. I don’t think he’s interested in my opinions, or considering contrary views.

‘How are you going to tell them all apart?’ I ask. ‘The spies and the cobblers, the killers and the poets?’

The Sick-Man turns his dark, hooded eyes on me. The dark pupils have no sheen or sparkle. They swallow light and give nothing back.

‘It is not necessary to tell them apart,’ he growls. He shrugs.

‘No?’

‘No man, no problem,’ he says. ‘Death solves everything.’

‘Yes?’

Sometimes he talks in riddles. So, there’s no guessing what he means, or what cloudy thoughts swirl round in his head.

‘I have taken to you,’ says the Sick-Man. ‘You have a soothing smile and a kind heart. You remind me of my dead son Arkady.’

‘I do?’

‘You are passably clever. And yet dismally stupid. You aim to please but you lack ambition. You have no guile. People trust you. It’s a rare combination. And there is something calming and comforting about your presence. Would you like to make yourself useful?’

‘Thank you, Comrade,’ I say. ‘I would.’

‘Then, I will appoint you to a position, here, in my household.’

‘A position?’

‘A vacancy has arisen.’

‘Sir?’

‘It is an important position. You will be my Food-Taster, Technician First Class.’

‘Yes, sir?’ I ask. ‘What would I do?’

‘You taste all my food before me. And sip all my drinks. Just to check they are fit for me to consume. Ensure they haven’t been tampered with.’

‘Is this a new position?’ I ask.

‘I had a food-taster before …’ he concedes. ‘And one before that … And one before that. But none of them stuck to the task …’

‘No?’

‘They were all allergic to toxins. Each in his different way. One was sensitive to strychnine. And another was allergic to cyanide.’

I consider the offer. I consider it from all angles. I like food. I like it very much. And there are worse jobs than eating the same fine foods as top-rank personages, such as Marshals, Deputies, Ministers, General Secretaries and Ambassadors. And I’d always dreamed I would, one day, overcome my challenges to hold a post of importance. Besides, I sense, refusal is not an option.

‘I will eat for you and the Motherland like a patriotic Slav,’ I say.

‘You will have the freedom of the building. But you will make yourself available as and when I require, at breakfast, lunch and supper …

‘Also you can report back to me whatever is said in my house. You will join the Special Security Section. In particular you will listen out for whatever is said behind my back by Comrade Bruhah, Marshal Krushka, Deputy Bulgirov and Secretary Malarkov.’

‘Yes?’

‘They attend in the evenings. They hang around. They take supper with me. They pass themselves off as friends. They are easy to recognise. I call them the hyena, the pig, the donkey and the goat … They are not so clever as they think. They will speak freely in front of you, because you are a fool and a child … They will assume you can’t understand what they say, or decipher what they mean …’

He reaches to the desk. He scribbles on a sheet of paper, a note in spidery green ink and passes it to me. It reads –

The bearer is my personal food-taster.

Technician First Class, Yuri Zipit.

Be advised. He is a harmless moron.

Afford him every assistance he requires.

He has the freedom of the house.

Help him and you help me.

Thwart him and you thwart me.

Josef Petrovich

General Secretary

‘Go now,’ he says, ‘I will sleep. And if Bruhah asks you what we spoke about and he surely will – be warned – tell him I talked about the Mingrelian Conspiracy.’

‘Will he understand?’

‘He will, indeed,’ says the Sick-Man, ‘because he, himself, is the Mingrelian Conspirator.’

‘Really?’ I say.

But there’s no answer.

The Sick-Man’s eyes have already closed. He snorts, then begins a slow rumbling snore, so I turn away, walk to the door. I let myself out.

Now I must go and find Papa and tell him the good news. Though I must not seem to brag.

I walk out with pride. For I came into this room as a nobody, and left as a somebody, as a person of standing, as a Food-Taster, Technician First Class, to the General Secretary of something-or-other, who is a man of some importance, well connected in the Party.

5. THE FOUR IRON-MEN

Comrade Bruhah is leaning against the wall at the end of the corridor. Then he’s striding towards me. Fast and furious. I suppose he’s been waiting for me to emerge from the Sick-Man’s room. He wears a poisonous frown on his puffy yellow face, like a cane toad (Rhinella marina).

‘Have you seen my Papa?’ I say.

Bruhah ignores this. He lays a stern, stiff arm on my shoulders. Well, in truth, it’s more like a headlock, with his arm circling my neck. I feel like I’m back at breaktime in school, bullied all over again.

‘Why do you smile all the time?’ he snaps. ‘Do you think the world’s a pleasant place? Do you think I’m here to be kind to you? Do you think everyone’s your friend?’

He drags me along. I’m bent like a hinge. He stoops and presses his shiny, warm

face close to mine. I can smell pepper mint, vodka and onions, and a hint of musky perfume besides, as if he’d been rubbing against something more fragrant than himself, most likely a woman.

‘The Comrade likes you, you shitty, little, maimed runt,’ he says. ‘Why on earth would that be?’ He looks to his watch. ‘You’ve been with him for four hours.’

‘We play draughts … We swap stories … We share memories …’ I say. I am gasping because the Marshal is pressing the air from my neck. ‘We have things in common …’

‘You do?’

‘We both have a gammy arm. His mother went missing, like mine. He got called names at school, like me …’

‘You have his confidence?’ Bruhah steps back, releasing my neck. He looks bemused. ‘He tells you things? Personal, private things?’

‘Yes.’

I tell him of my appointment. I say I am to be the Boss’s food-taster. First Class. And, if necessary, to die to save him for the Motherland.

‘The Comrade is not himself, these days. He is sick,’ says Bruhah. ‘In his head. We must not take advantage of his good-nature. We must help him as much as we can. So you must make me a promise.’

‘Comrade?’

‘Listen carefully to whatever he says. Everything. And report it back to me. Nothing is too big to tell. Nothing is too small.

‘Yes?’

‘And, in return, I will look after you.’

‘Thank you,’ I say.

‘You will need looking after,’ he says. ‘You will need it very badly.’

‘I will?’ I ask. I had no idea.

‘Close your eyes,’ he commands, ‘and think of the best that could happen to you …’

Yes. I see it now. I’ve returned home from school. But there are three suitcases in the hall, not two. Mama is returned to us, out of the blue. I hear her shriek and giggle and Papa’s deep laughter.

‘Now,’ Bruhah pinches my shoulder, ‘think of the worst thing that can happen …’

I wince. As before, I return to the apartment. But in this imaginary scene there is only one suitcase. Yes, Papa has been taken from me. Who knows where.

‘I know exactly what you’re thinking,’ the Marshal tells me. ‘Every last detail. I can read your shallow child’s mind. But you have not thought hard enough, because I can make the worst far worse, and I can make the best even better …’

‘You can?’

‘That is my business. Making a person’s life better, or unbearably bad, depending on what he deserves.’

‘Oh.’

‘So anything is possible for you, Yuri, you foul-smelling dollop of shit. The best and the worst, North of Hell, and South of Heaven, and all points in between. You must simply do as I say.’

‘I must?’

‘Do you know what I do in life?’

‘No.’ I admit it.

‘I am an artist. But where a painter uses colours and a potter uses clay, I use pain and fear. For I am a terrorist.’

‘You are?’

‘I terrify people. I arrest them. I punish them. I break them. I crush their bones. I pop their eyes. I shred their souls …’

‘Ouch,’ I say.

‘Sometimes they kill themselves before I can start. They drop dead of fear before I have a chance to lay a finger on them. But I do not get other people to do my dirty work.’

‘No?’

‘If a man needs shooting, I do it myself. If a man needs his finger nails pulling off, or his eyes popping out, or his bollocks kicking off, I do it myself. I do it for the Motherland. I do it for Socialism. And I do it for my own satisfaction, as a job well done.’

Of course, I don’t believe him. He’s just playing around, trying to scare me. Nobody would deliberately hurt another person. Not in those needless, ugly, cruel ways.

Papa says most hurt is unthinking – inflicted when people are not vigilant enough to the other person’s feeling, and act without kindness, and without first considering the consequences.

‘Stand still,’ says Bruhah. ‘Now observe how it is …’ He smiles. He slides finger and thumb either side of my nose. It tickles, until he tightens his grip, then gives a sharp jerk, with a twist.

It is an evil conjuring trick. There is the screech of a branch being bent. Then a sharp snap, like a twig underfoot, which echoes through all the bones of my skull. It feels like a bolt of lightning has passed through my face. Golden flashes spark out in all directions. I want to retch. I feel a hot spray of blood in the back of my throat.

I slump against the wall. I think I pass out for some seconds.

‘That’s your nose,’ he points out. ‘It was whole … but now it is broken.’

‘Aaah,’ I say. Blood is trickling over my lips, and down my front.

‘Understand. The whole of your body is like this.’

‘Ugh?’ I sniff warm clots of myself down my nose, into my mouth, then swallow.

‘Everything whole can be broken, inside and out. Skull, liver, teeth, heart, spirit. And, with each break comes more pain … worse pain … But that was nothing. It was only your nose. So it doesn’t matter …’

He releases me. He pats me on the shoulder and smiles. ‘That was a tiny thing compared to what I could do to you, if I wanted to hurt you properly, like an artist …’

‘No need,’ I protest.

‘So, you will tell me whatever the patient says to you.’

‘Yes,’ I sniff.

‘When you talk to the Comrade, there is a right way and a wrong way to do it.’

‘Sir?’ I’ve lifted the end of my shirt to my nostrils to block the drip of blood down my front.

‘Look him in the eye. But don’t look at him too long in the eye … Always tell him the truth. But don’t tell him too much truth … Do not show any weakness. He despises the weak. But you should not show strength either. It will make him ill at ease. Say whatever you want, by all means. As long as it’s what he wants to hear. Do you understand me?’

‘Yes, sir.’ I sniff hard and then swallow warm globs of my blood.

‘Good,’ he says, ‘I think we are going to be very good friends. Here, I think you deserve a prize …’ He reaches into his pocket and hands me a thin strip of silver foil. ‘I give you this because I am a kind man who loves children …’

I sniff. ‘Thank you, sir. What is it?’

‘It is called chewing gum,’ he says. ‘It is a gum. For chewing. So it goes in your mouth. It comes from Amerika. It is called Wrigley’s Spearmint. You are very fortunate. You slither of shit. There are only seven packets in the entire Socialist Union.’

Although Marshal Bruhah is very rude and a hurtful nose-breaker, I realise this must be because he is an unhappy person and has many worries in his life, perhaps with special responsibilities, annual accounts, agendas, paperwork, troubles and difficulties, such as make Papa tetchy too.

Papa always told me, ‘Everyone has their reasons, Yuri. So, if you don’t understand someone’s actions, you simply haven’t understood their mood, their character and situation …’

‘Thank you, sir,’ I say. I let my mouth play around with it, and my teeth sink into this strange grey, gummy thing, which passes for a delicacy in Amerika. ‘… It’s very chewy. And very minty …’

And yet oddly hard to swallow.

‘Come,’ he says, ‘I lack a mother’s kind touch. Matryona, here, will look after you even better than I can …’

*

Matryona is the housekeeper, in a black sack of a dress with a white apron. She is plump and pink and smiley. She seems broader than she is tall.

‘Oh, the poor, broken, bleeding boy,’ she says and tousles my hair. ‘And your poor, bleeding nose.’ Then she hugs me. She squeezes my head into her hot bouncy, powdery bosom. Sunk deep in her musky flesh, my cheeks burn and I hear her heart like the close tick of a clock.

She says I will need my nose twisting back straight, and then cotton wool up each nostril. Then a bed. She says I can sleep with the oth

ers in the men’s staff dormitory.

We climb a set of stairs to the first floor. We wander down a long corridor. We find a long darkened room arranged like a hospital ward, with low metal-framed beds around the walls, and a long table down the centre.

Five of the twelve beds are taken. I take the empty bed close to the door.

‘Papa?’ I whisper to the dark serenade of snores. But the dark gives up no reply. He’d answer if he was here. I will have to wait for the morning to find him.

I try to be positive. I think what Papa would say. That all will seem better next day. That a broken nose is better than a broken skull. That a dull throb is better than a screaming, shooting pain.

My head hits the pillow. I’m gone.

*

I am woken at seven by the chatter and clatter of the household rising. There is a chorus of coughing, spitting and bickering. There is the smell of warm, moist, leaky bodies. There’s the stamp of boots on wooden boards.

I follow the staff down to the canteen to take my breakfast.

I look around for Papa but he is nowhere to be seen.

I am alone in their company. No one returns my looks or smiles. So I take a solitary seat at the side, at the end of a long pine refectory table.

I have been there a few minutes when a shadow falls across me and someone sits down beside me and lays a plate of floury, yeasty-smelling, steamy muffins on the table.

‘Good morning, kid,’ he says.

I turn to see the strangest sight. It is only the spit of Comrade Josef Iron-Man, all over again.

But a different spit.

This is not the thin, sick, grey-haired Iron-Man I met the night before. This is a raven-haired, tall, thick-set, youngish Iron-Man with deep scarlet pits on his cheeks.

He extends a giant hand to shake mine.

‘I am Felix,’ he says.

‘Yuri,’ I say. ‘Happy to meet you.’

‘Tell me …’ he frowns, ‘why do you keep them there, of all places?’

‘Keep what?’

‘Those hard-boiled duck eggs …’

‘Pardon?’

‘In your ears.’

‘Excuse me …’ I say

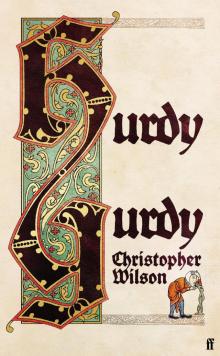

Hurdy Gurdy

Hurdy Gurdy The Zoo

The Zoo