- Home

- Christopher Wilson

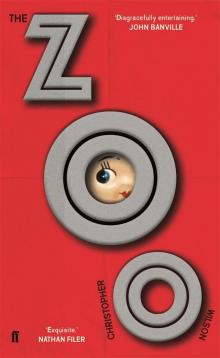

The Zoo Page 6

The Zoo Read online

Page 6

‘Here …’ He taps my right ear and produces a still-warm egg from his palm. ‘And here …’ He touches my left ear and discovers a second egg. ‘You know what would be best?’ he says. ‘Everything considered …’

‘What?’

‘I think we should eat them for breakfast with these hot buttered muffins.’

This sounds an excellent plan. To share my eggs and his muffins. We eat in satisfied silence. The egg yolks are rich as molten butter and golden as the sun.

Then another being joins us, parking himself on the bench opposite, which creaks under his lowered weight. I look up to see who it is.

Yes. Only another one. No lie.

Another Comrade Josef Iron-Man.

But a different-looking one. This one is stout, of middle years and middling tall. I am struck by his large, fleshy, cabbage-leaf ears.

‘This is Rashid,’ Felix tells me.

‘Pleased to meet you, Comrade,’ I say.

‘Good morning, young rascal,’ says Rashid. ‘What brings you here?’

I tell them I came to help my father, a Professor of Veterinary Science. I say we became separated. I ask if they have come across him.

I describe him. I say he is a tall, absent-minded man, with a bald spot, a stoop and an astrakhan collar, and carries the scents of scorched wool and pipe tobacco. I explain he is especially clever, with a profound knowledge of Cordate Neurology.

‘I haven’t seen him,’ says Rashid. ‘Cordate Neurology, you say?’

‘Nor I,’ says Felix. ‘What was the purpose of your visit here?’

I say we came in a medical capacity, to treat a sick man who looks like …

Then I fall silent. I am loath to tell them. For fear of causing offence. Or sounding rude. Or stating the obvious.

‘Forgive me for saying so,’ I explain, ‘but the sick man looks like Comrade Iron-Man.’

‘Yes?’ asks Felix. ‘What on earth do you mean, he looks like Comrade Iron-Man?’ He seems bewildered by the notion. ‘Are you suggesting he looks more like Comrade Iron-Man than me? Or Rashid, here?’

Both the Comrade Iron-Men look surprised. And hurt. That there might be a more Iron-Man-like Iron-Man than them. Big-Ears and Pock-Face exchange bemused glances.

Well, I don’t want to cause offence. I want to answer politely. But it’s hard to find the right words to tell people apart when they all look like Comrade Iron-Man, while they also look like themselves.

‘Well, you both show a fine likeness to Comrade Iron-Man, to be sure … But he does too …’ I explain.

‘How do you mean, exactly?’

‘He had brushed back hair, like you both. And a moustache like you. And scars like Rashid. But smaller ears. And older-looking than both of you. And with a twisted left arm …’

‘Did he talk?’ asks Big-Ears.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘He sounded just like Comrade Iron-Man himself, when he’s talking on the radio. Except he used a lot of ugly, rude words.’

‘A talking Comrade Iron-Man …’ Big-Ears shakes his head. He whistles in awe.

‘A swearing Comrade Iron-Man,’ says Pock-Face, clearly bewildered by my news, ‘who’s had voice-training. And taken cussing-classes, and blasphemy lessons.’

‘If they’ve taken on a new Talker,’ says Big-Ears, ‘who can swear like the Boss himself, there are repercussions all down the line, for Statues and Mutes, and the likes of us.’

‘It stands to reason.’

‘We’re just Walkers, you see,’ says Felix. ‘And Long-Standers …’

‘And Comers and Goers,’ says Rashid.

‘Excuse me?’ I say.

‘We are doubles,’ says one. ‘For the Big Boss.’

‘And triples, sometimes,’ says the other. ‘We stand in for him when he needs to be in different places, all at the same time. There are five of us, at present, all told.’

‘So he can be in the Crimea, on affairs of State,’ says Rashid, ‘while we watch the tanks roll by for him, for hours on end, in some procession around Martyr Square while, at the same time, opening The Red Proletariat Printing Works in Novgorod.’

‘Or supposing there’s word that some foreign agent wants to take a pot-shot at the Boss. We can leave in the limousine at the front, and take the flack, or catch the bullet, while he slips safely out at the back.’

‘Sometimes, when the Boss spends the day here at the dacha, we each repose in one of his sitting rooms. It is quite relaxing. We can sit in his chair, and read Pharaoh by Boleslaw Prus, which is one of his favourite books, or The Combat History of the 2nd Guards Tank Army from Kursk to Berlin: Volume 1, which is another. But he will not have us smoke his cigarettes, or drink his mineral water.’

‘That way, if an assassin breaks in, he will not know who to shoot for the best. Or he’d be tricked into killing the wrong Comrade Iron-Man, which would be a great blessing for the Motherland.’

‘But we aren’t allowed to talk as the Boss, in case we say something wrong.’

‘Once, a substitute-Boss drank too much at an embassy dinner, and got carried away. He made under-the-table approaches, of an intimate kind, to the wife of the Swedish Ambassador. Then he entered into a hasty, ill-considered treaty with the Amerikans …’

‘A fatal mistake.’ Rashid holds fingers to his temple as if firing a pistol.

‘So, now, we’re all sworn to silence,’ says Felix. ‘It’s safer all round.’

‘Well, this old man never stopped talking,’ I say. ‘He had a foul mouth. And he shouted at Marshal Bruhah. He called him a donkey’s arsehole.’

Rashid raises his eyebrows. Felix frowns and rubs his chin. They eye me in silence.

‘Do you know what, kid?’ Felix says at last. ‘I think you maybe met Him. The Boss himself.’

‘So, he’s really short, then, with foxy eyes?’ I say. ‘Smokes a pipe. And smells like a goat?’

‘Beats me,’ says Felix. ‘To tell the truth, I’ve never met him.’

‘Me neither,’ says Rashid. ‘But he passed me once on the staircase in the Palace of the People. At least, I think it was him, but you never know … It might have been another one of us … For we both saluted each other.’

‘It’s our job to be him, you see,’ says Rashid, ‘in his absence. Not pass the time of day with him.’

‘He has more important things to do,’ says Felix, ‘than waste his time chattering with nobodies like us …’

‘He has to look after his peoples,’ says Rashid.

‘He has fifteen Socialist Republics to govern,’ says Felix, ‘from Armenia to Uzbekistan.’

It makes me shiver. Looking back, if I’d known from the start that I was talking to the real Josef Iron-Man, I’d have been more careful what I said, and how I said it.

*

Enjoying the luxury of my boiled egg breakfast in the company of my two new friends, and two most favourite Comrade Iron-Men in the whole wide world, I was not surprised when we were interrupted by a man who introduced himself as Comrade Alexei Dikoy, Director at The Kapital Arts Theatre.

In appearance and clothing, he too resembled no one so much as the Great Father, Gardener of Human Happiness, Kind Uncle, Man of Iron, Comrade Josef Iron-Man himself.

He frowned down at me. He scowled at Rashid and Felix. He told them that they must make themselves ready to commence the day’s training.

He said they would be employing the methodology of his personal friend and mentor, the deceased theatrical director Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavsky, may he rest in peace, the confidante of Anton Chekhov, Leo Tolstoy, Nicolai Gogol and Alexander Pushkin.

He said that they would use the staff recreation room as rehearsal space. He said they would commence in two and a half minutes. And that we should exit the green room immediately. He said they would have to draw on their emotional memory and the lived truths of their lives.

He said I should come too, and make myself available to fetch refreshments from the kitchen, and sweep the floor,

and dog’s-body as required. It did not occur to him that I might have a father to find, or any business other than serving him.

I asked him, in passing, if he had come across my Papa, Doctor Roman Alexandrovich Zipit, in his travels around the house.

‘Who is he? This father of yours …’

‘He is a vet. He is a famous Elephantologist.’

‘Then I have not met him. The Theatrical and the Elephantastical are professions that rarely answer any urgent call to convene on common ground.’

‘Shame,’ I explained. ‘It’s just I’ve lost him.’

‘How old is he?’

‘Fifty-seven-and-three-quarters,’ I said.

He nodded solemnly. ‘Don’t worry. The solution is in the age. Having reached this far in life, he shows a capacity to continue without you. He’ll survive. He’ll turn up. Relatives always do, whether you want them to or not.’

He gave me a downward expression of sympathy and patted my crown.

Of course, I followed in his wake, carrying a small samovar, as he’d instructed.

I have to say that of all the Iron-Men that I had met so far, Comrade Alexei Dikoy was the most commanding, natural and life-like, and much more realistic than the real thing, which seemed old, tired, grumpy, dirty, smelly and worn-down.

His walk was just like the Comrade Iron-Man we saw in the newsreels. His face wore a greatness and a calm. His presence was like a charge of electricity. It made the hairs rise on the back of my neck. I could hear the beat of my racing heart, throbbing in my ears.

He was an Iron-Man you would follow, barefoot through The Cold Lands, to the very gates of Hell.

‘Come along, you towering dwarfs, you galumphing peasants …’ he barked at Felix and Rashid, ‘today you will learn to play not a human being, but a granite monument.’

6. IMMORTALITY FOR BEGINNERS

When your father is a Professor of Cordate Neurology, and entertains Academicians, and suffers writers, and keeps company with intellectuals, and is happy to hear actors spill their favourite stories all over again, and doesn’t draw the line at artists, even though they’re convinced the world owes them a living, then life becomes an education in itself, and there’s a lot you learn just by listening to what is said around you, over your head, behind your back, through thin walls, and straight to your face.

For instance, this is a story I overhear Papa tell to Comrade Anna, Curator of Large Mammals –

There was an international competition for the best book about elephants.

France entered a lavishly illustrated volume called The Sex-Lives of the Elephants.

England presented a treatise called ‘Elephants: a Business Model’.

Germany submitted a twenty-four volume work entitled The Theory and Praxis of Elephantology: an Introduction.

The USA furnished one million copies of a leaflet for a prize-draw, ‘Win an Elephant. No purchase necessary.’

Our Motherland sent three volumes, entitled –

Vol. 1: The Role of Elephants in the Great October Socialist Revolution.

Vol. 2: The Happy Life of Elephants Under the Progressive Socialist Constitution.

Vol. 3: The Union of Socialist Republics – Motherland of Elephants.

Papa also tells me about the sorry life of elephants in the USA and some of the worst crimes Amerikan history has committed against them.

He tells how Thomas Edison, the inventor, in 1903, electrocuted an elephant called Topsy at Luna Park, Coney Island, and filmed the murder to show in kinemas, to demonstrate the danger of the alternating current, so people would buy his competing version of electricity – the direct current – instead.

And Papa tells how in 1913, in Erwin, Tennessee, they gave a courtroom trial to an old elephant called Mary, after she had defended herself against an attack by her cruel handler. And the jury found her guilty of murder. So, then, they executed her – hanging her, by hoisting her by the neck from a railway derrick.

*

But we don’t just talk elephants, Papa and I. We have many other interests besides. We talk at length about zoos, supper, good manners, science and football too.

Papa tells me how Comrade Iron-Man himself took a deep interest in matters veterinarian, biological and experimental.

Papa tells me how his very own teacher, Professor Ilya Ivanovich Ivanov, had invented artificial insemination, which is a special way for animals to have sex – but with most of the pleasure taken out, and without even needing to touch each other.

And had then been awarded a grant, from the Politburo itself, with Comrade Iron-Man’s personal approval, to create a new type of being, a human-primate hybrid. Because that way the Socialist Union could defend itself with a new army, an invincible fighting machine made up of soldiers who were half-monkey, half-human.

It was just a matter of finding the right balance. Because the generals had seen how soldiers who were all-human could turn out timid, sensitive to pain, fearful, and fussy about food. While monkeys liked fighting and would eat any old rotten garbage for rations, but wouldn’t take orders, wear berets, march in formation, care for their uniforms, salute officers, or take to military discipline.

So Professor Ivanov goes to Conakry, Guinea, to the Pasteur Institute, to put some tough monkey spirit into the soldier-mix, and soften their wild apishness with some human obedience.

First off, he tries to get female apes pregnant with human sperm. But it never seems to take. As if there’s always some obstacle, or barrier.

So, Ivanov comes back to the Motherland to try the reverse procedure. He squirts the sperm from orangutans into Socialist women. But the beasts never succeed in getting any Socialist ladies pregnant, besides they didn’t take to the Slav climate and diet, so they kept on dying carelessly. Even Ivanov’s favourite, called Tarzan. And by the time he’d run out of orangutans, and monkey gizzum, he got arrested, then died of a stroke.

But Trofim Lysenko, who was head of Genetics at The Socialist Academy of Sciences, told Comrade Iron-Man you could teach plants and animals to enjoy the Slav weather. And that they would pass the lessons on to their offspring. Who would learn some more, and pass it on to their young too. So, eventually even coconut and pineapple and oranges could adapt to The Cold Lands, and learn to love the snow.

But, as it turned out, it was hard to teach plants they enjoyed sub-zero cold, and there were lots of bad harvests, year after year, without any vegetables learning much about The Cold Lands, or passing on a love of the freezing Motherland to their young.

*

In my class at school our Mathematics teacher – Professor Pavel Popov – is known to be strict. But I would not say he is a quarter as strict, nor half as sarcastic, as Comrade Theatrical Director Alexei Dikoy when he is attempting to teach Rashid and Felix to act like the Great Father, Josef Iron-Man.

‘When I ask you to walk across the room like Comrade Iron-Man,’ the Director barks at Felix, ‘I do not ask a lot. In fact, I ask very little. But I do demand that you use your emotional memory and let it inform your method of physical actions. And I ask that you incorporate the given circumstances that we know about this character, Our Leader …’

Then the Director starts to discourse on the background circumstances that make Comrade Iron-Man walk as he does – that he is seventy-odd years old, that he comes from Georgia, that he has two toes joined together on his left foot, that his father was a cobbler, and his mother a housemaid, that he survives smallpox as a child and damages his left arm as a young man, that he attends the Tiflis Spiritual Academy, that he joins Comrade Lenin and the Bolsheviks, that his young wife bears him a son but then perishes of typhus, that he fights in the Revolution, that he then joins the Reds to fight the Whites, that he joins the provisional government …

And when you think the Director is quite finished giving Iron-Man’s background for walking on his feet that way, he starts again on his objective and then on his super-objective. And what is his through-line? And what about th

e magic-if?

Above all, he demands that Felix and Rashid ask themselves the fundamental questions about the walking-complex –

Why does Iron-Man cross the room? What is he saying to the world, by crossing the room?

And in the end, having crossed the room, what does he hope to achieve by it?

‘Now, I ask you one more time. And I ask you politely. And I ask you patiently, in a spirit of Comradeship, as one artist to another …’ says Director Dikoy, ‘cross the room like Comrade Iron-Man, but remember you are the Man of Iron, Leader of the Socialist World, that your Iron-Will has crushed Hitler … but that there is yet a tender side to your nature that includes a love of children, family, country, Mozart, particularly the later piano concertos, especially Number 21 in C Major, and literature, including the short stories of Chekhov, and most especially The Lady with the Dog …’

You can see that poor Felix is daunted and confused by all this information, and does not know quite how to use it for the best, to move his feet, because he steps on his untied bootlace on his way to tripping over the samovar.

‘Stop. Stop,’ the Director screams. ‘Stop that dreadful shuffling and stumbling …’ He is holding his hands across his eyes, to avoid witnessing the travesty of Felix’s movements.

‘Sorry,’ says Felix, lamely, picking himself up and dusting himself down.

‘It is not your fault,’ the Director admits. ‘You are simply a peasant, a children’s entertainer, a juggler from Yekaterinburg, with no more to offer than a face that fits … We are getting too far ahead of ourselves … You cannot move your arms properly. Not yet. You do not know how to work your legs. You have no balance. Your centre of gravity is skewed … And you do not understand how to carry your head …

‘We will take things back to the very basics. First we will have to learn to breathe like Comrade Iron-Man …’

*

My first meal with the Boss is a breakfast. I am required to taste all the foods laid out. Then, if I am not sick within thirty minutes, he knows the meal may be free of toxins and safe to eat.

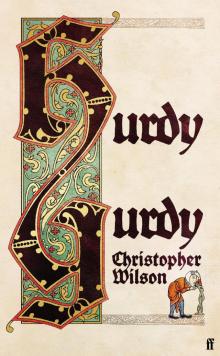

Hurdy Gurdy

Hurdy Gurdy The Zoo

The Zoo